This deconstruction was one of the first to be executed by The Naked Watchmaker platform in 2017. Today (2021) it has been revisited and expanded upon.

The Reason

An example of how many brands acquired existing generic movements and made them their own by personalisation, altering the finishing and making technical changes to the construction. Here Rolex used a classic Valjoux movement.

The dial remains the original and the overall design is classic Rolex without following the DNA they became known for through the iconic Oyster case.

The total number produced of the Valjoux 23 and the later Valjoux 72c was 126,583 examples.

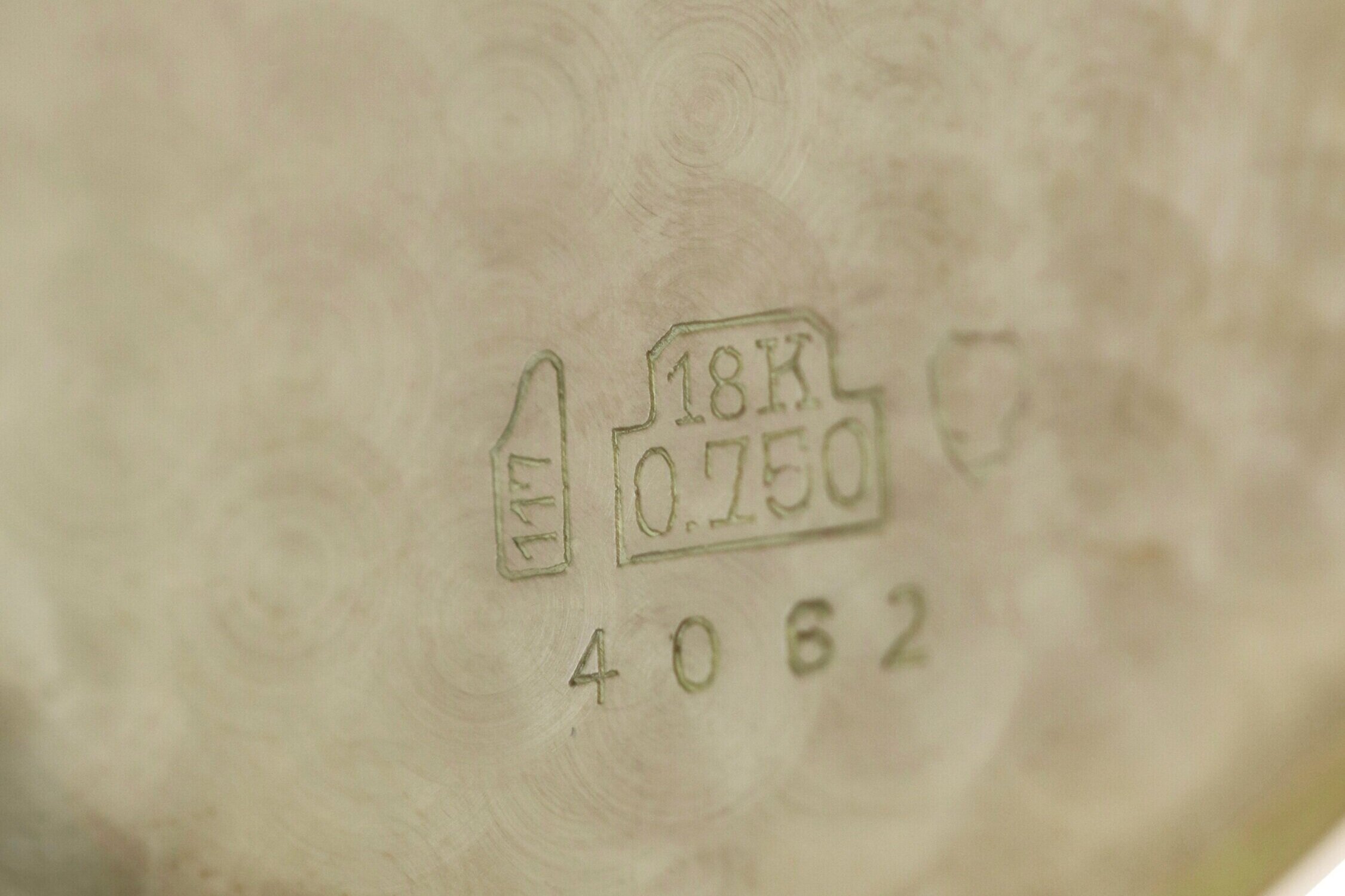

A manual wound Rolex chronograph ref: 4062, with 30-minute recorder at 3 o'clock in an 18k yellow gold case with coin edge decoration.

A solid case back, made before the advent of sapphire and exhibition glass case backs on wristwatches. (Many early pocket watches would often have a solid outer case back that could be easily opened revealing a second glass case back allowing the movement to be safely viewed.)

The case back snaps in place on the case centre and is dust but not water-resistant possessing no seels. To remove the case back from the watch as shown below a small blade on a watchmakers case knife levers the case back off in the same way as is often executed with pocketwatches.

Case back removed

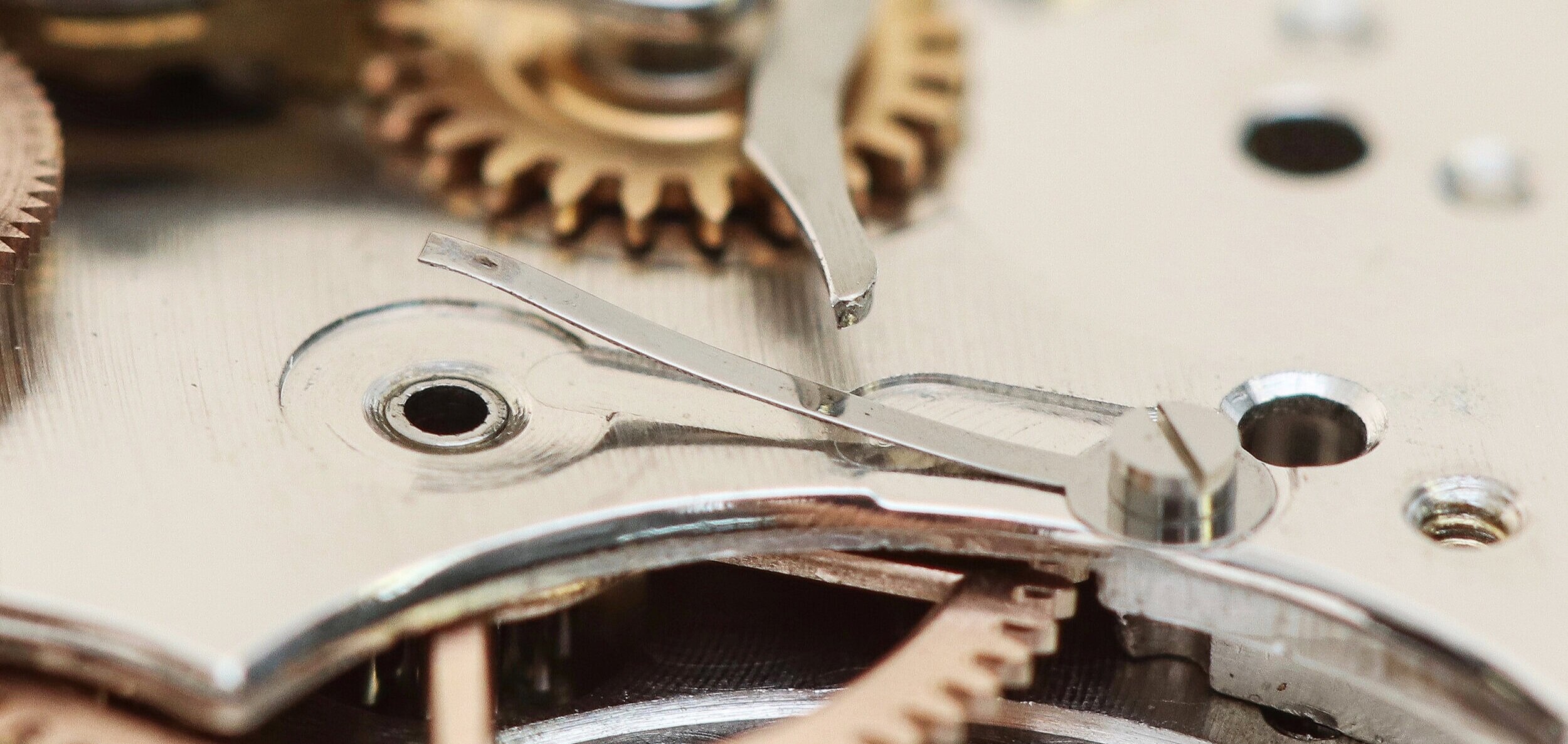

Column / Pillar wheel, The wheel that governs the start, stop and return to zero functions of the chronograph mechanism. Often associated to high quality or vintage chronographs.

The column or pillar wheel

The dial removed showing the setting mechanism, presently in winding mode. The movement remains in the case, the hands were removed once the bezel was taken off and the screws holding the dial feet in place, could be accessed from the rear of the movement, whilst the movement was still cased up.

Setting mechanism

Under the dial is the hidden surface of the main plate where additional branding is machine engraved.

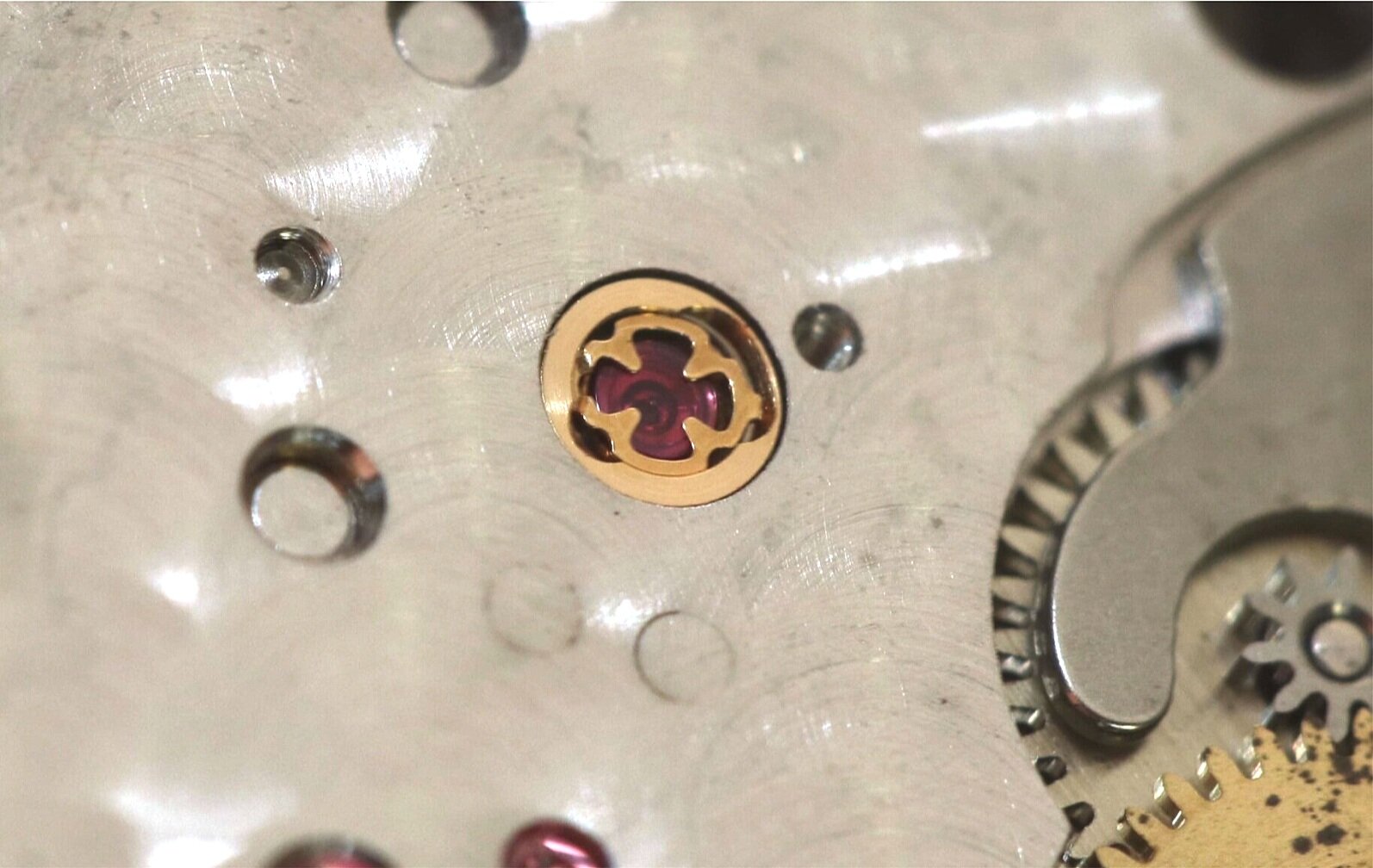

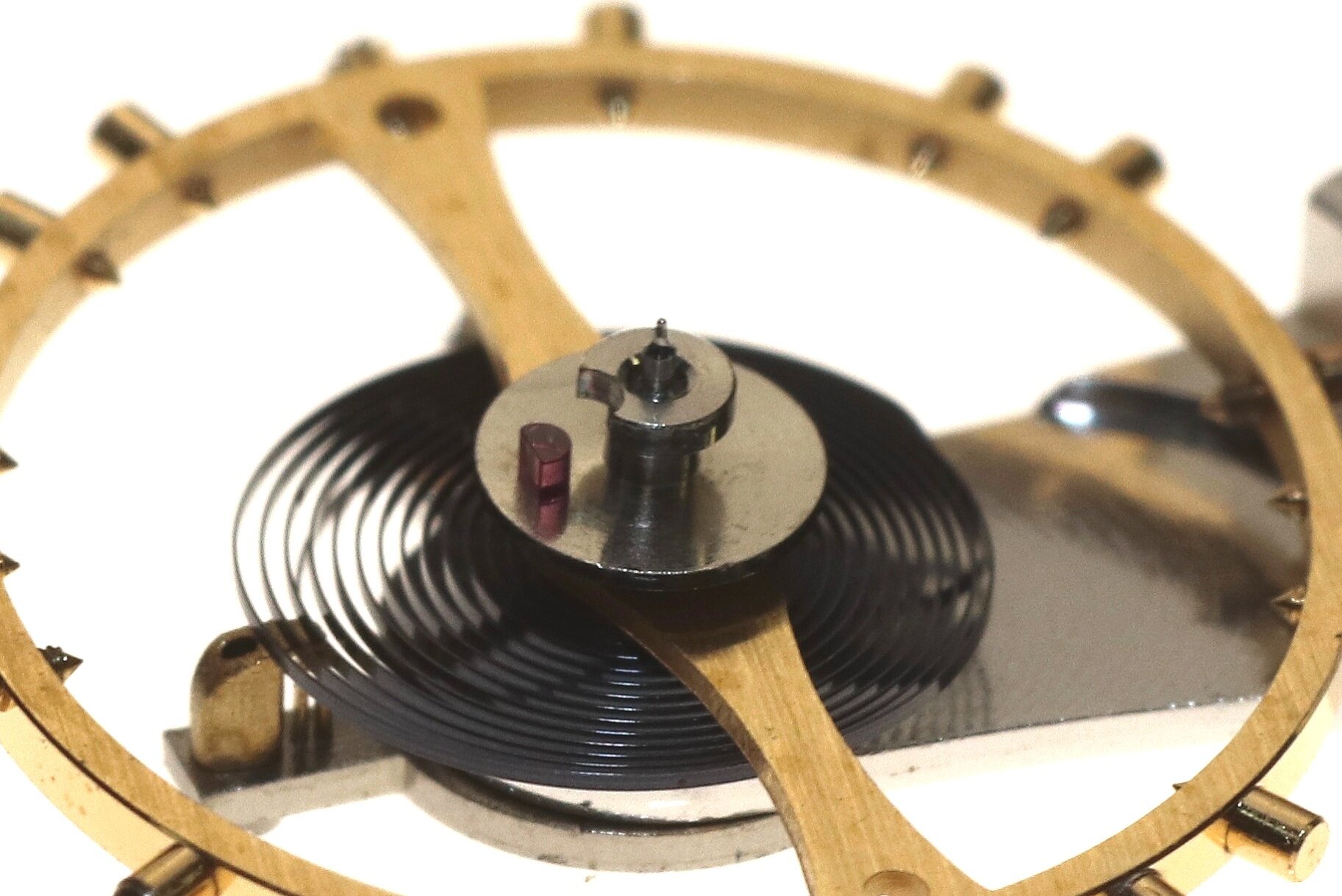

Below a shock absorber, a resilient bearing designed to dampen the shocks that are brought to bear on the delicate balance-staff pivots. Various shock-absorber systems are made in Switzerland under different names: Incabloc, Kif, Shock-Resist, etc. The earliest shock-absorber is probably the “parachute”, which was designed by A. L. Breguet (1747-1823).

Shock protection pushed into the main plate

The movement removed from the case

The movement partially dismantled, both the balance wheel and escapement assemblies removed as well as the chronograph and minutes wheel recorder.

Partially dismantled mvt

Side profile view of the movement showing the return to zero lever which is activated by 4 o’clock pusher on the side of the case.

The small rod protruding from the mainplate at the bottom of the image indexes the movement in the case.

The side view of the main operating lever that turns the column wheel. The rough finish on the side of the lever shows the part was stamped.

In the centre of the image is an eccentric plug upon which the rear end of the intermediate wheel assembly that turns the minute recorder wheel butts. The eccentric plug looks like a tall screw but has no thread, has an eccentric foot and is pushed into the bridge it sits with a trace of beeswax.

In the centre of the image is the eccentric stop

The calibre reference, Valjoux 23 found under the balance wheel stamped onto the main plate.

Calibre reference, Valjoux 23.

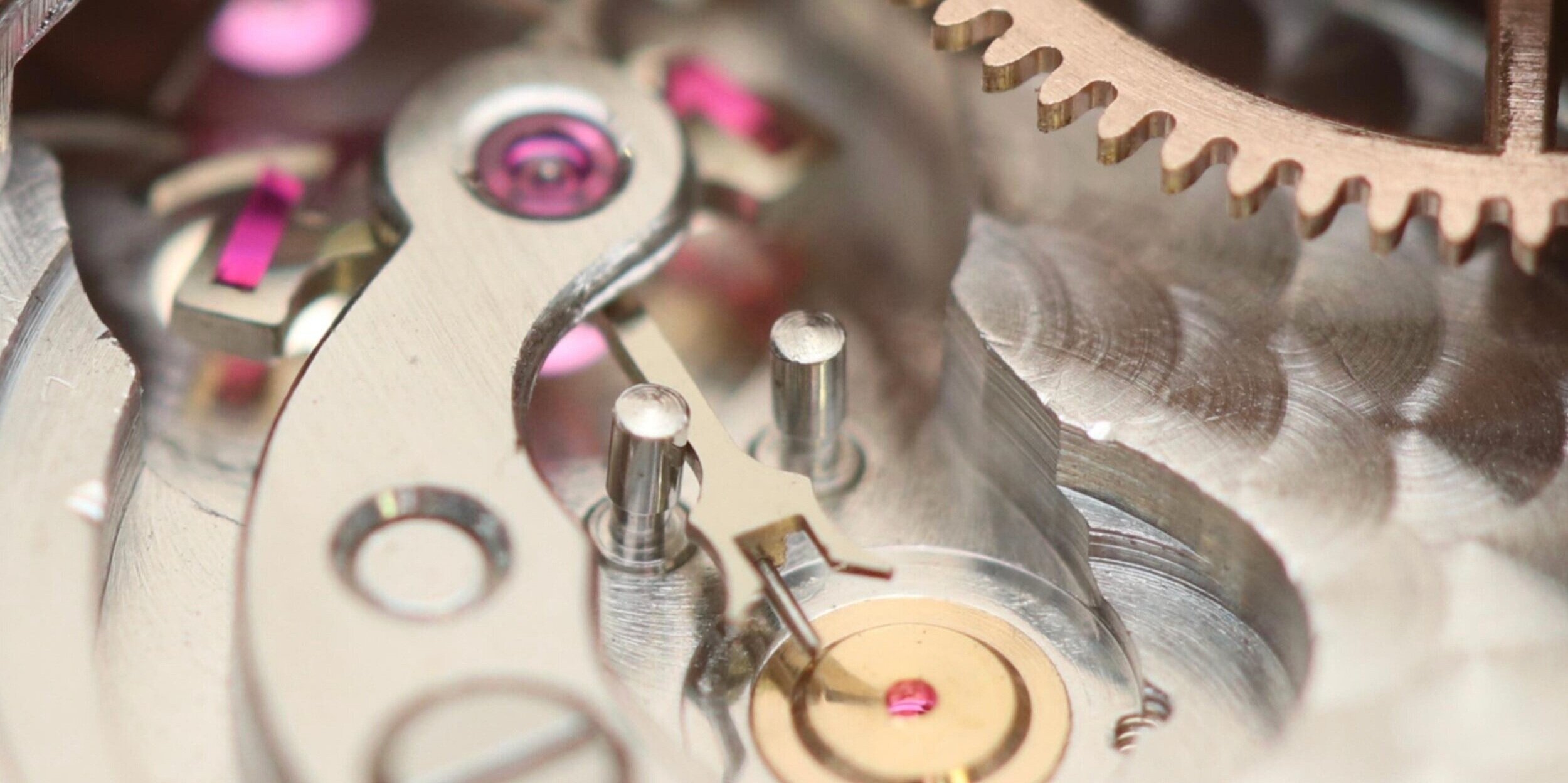

Interaction between the parts. The top lever, with a rounded beak next to the steel pin is the hammer piece. When this piece is activated in order to return the chronograph hands to zero it first pushes against the steel pin that is set into the brake that is holding still the chronograph seconds hand, so that the brake is freed.

In the centre of the image are two vertical ‘banking’ pins against which the Swiss anchor escapement rest. These pins are narrower at the bottom to allow them to be gently bent when the escapement is first adjusted in order to adjust the depth of the side-ways movement of the escapement.

Banking pins

The chronograph and minute recorder wheel bridge is often used to position the branding of the watch company. It is the most visible bridge to be seen situated at the highest point in the calibre.

The chronograph seconds wheel. This is the wheel the central chronograph hand sits on, the hand thats starts to move when the chronograph is first activated by the pusher at 2 o’clock on the case. The heart shaped cam is acted upon by the hammer lever in order to return the wheel and hand to a specific position that of ‘zero’.

Chronograph seconds recording wheel

The triangular shaped finger piece underneath the wheel that rotates once every 60 seconds, pushes the minute recorder wheel by a single tooth, representing one minute, via an intermediate minute wheel assembly.

The minute recorder wheel upon which the minute recorder hand will be pushed. The steel cam as with the above chronograph wheel is acted upon by the hammer lever in order to return the wheel and hand to the specific position of ‘zero’.

The dark coloured material below the steel heart shaped cam is to balance the equilibrium of the overall weight of the assembly.

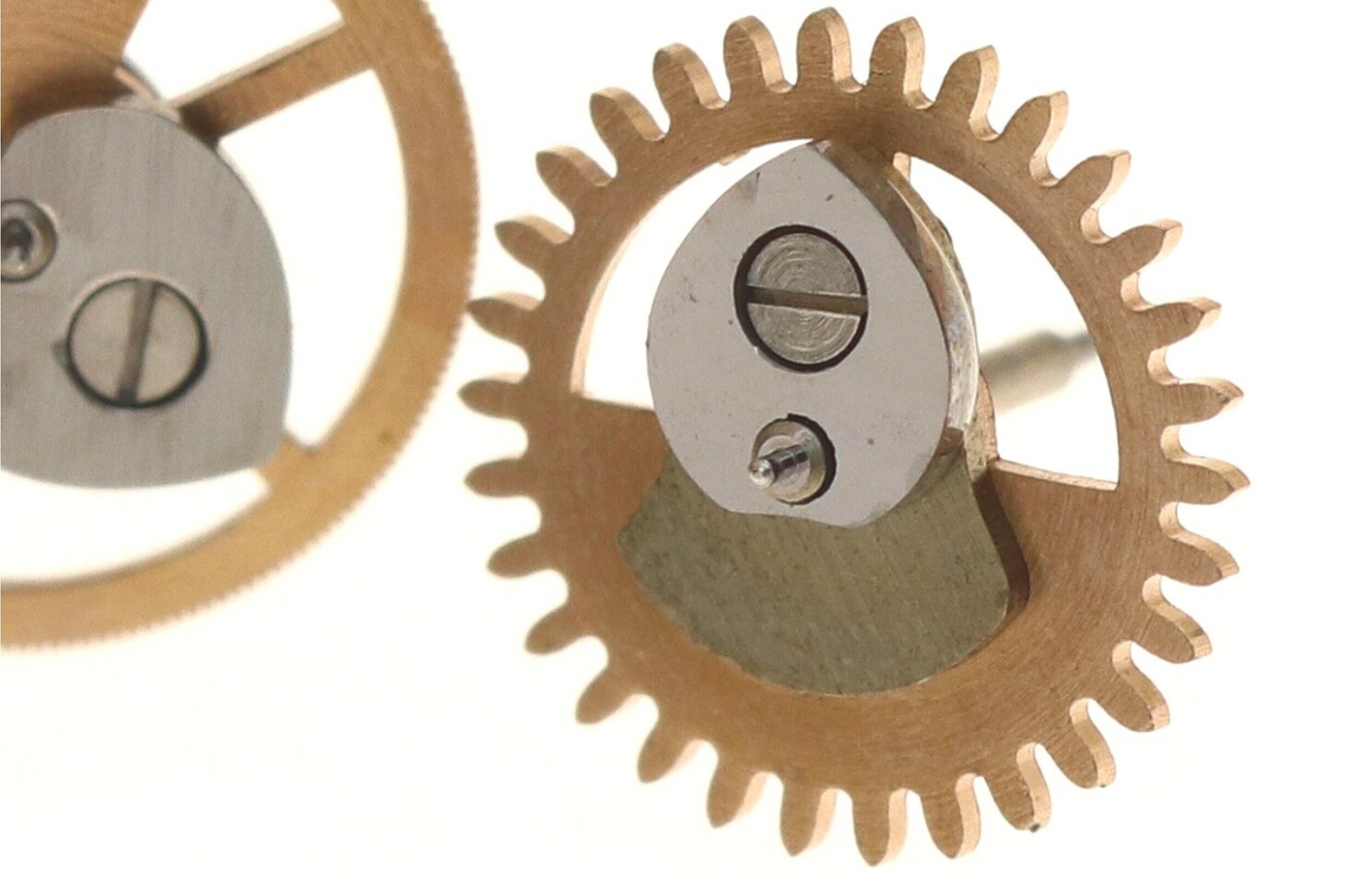

The pillar/column wheel removed from the movement. The screw to the left holds the pillar wheel in place, when it is tightened on the main bridge, the wheel remains free turning on the central shoulder of the screw. The pillars are lightly greased to reduce the friction where the contact of the diverse levers and springs rest on it.

Column wheel and screw

The small flat spring below acts under the chronograph seconds wheel adding a small amount of friction to remove any slack/play between the chronograph teeth. When either the gears are incorrectly depthed/meshing or this spring has insufficient pressure on the underside of the wheel the result can be visible fluttering in the chronograph seconds hand.

The chronograph hand friction spring

The return spring for the hammer and its screw. The screw is tall and forms a ‘stop’ for the hammer piece when in its rest position.

In the image below you can see the upper 4th wheel that drives the chronograph mechanism with its triangular profiled teeth. This type of profile is generally (although with exception) found on chronographs.

The centre eccentric resembling a screw head

The head of the eccentric plug, which looks like a screw head has been damaged by being adjusted with a wrongly sized screwdriver blade.

The chronograph seconds recorder wheel brake. When the chronograph is ‘stopped’ the slightly curved section to the top of the lever pushes against the teeth on the wheel prevently the hand for moving.

The chronograph wheel brake

The large bevel leads to the hole for the dial foot making the operation of assembling the dial into the movement easier.

Profile of the upper fourth wheel to the left. With the chronograph wheel bridge removed the chronograph wheel is lifted by the friction spring pushing underneath it.

The Swiss anchor escapement removed from the movement with its cock.

The upper balance pivot shock absorber

The steel screw locks in position the stud that in turn holds the balance spring.

The semi-circular jewel is the impulse jewel that receives energy from the escapement to drive the balance wheel assembly. The small ‘c’ shaped disc above it is the ‘safety roller’ that prevents the Swiss anchor from locking out of synch in case of knocks.

One of the timing screws requiring a specific form of tool of the same shape to adjust it. This system is still used today.

Star-shaped timing screw

The dial

The dial is has a patina resulting from a deterioration of the surface over the last 60 years. The case was never water resistant and the dots which were originally radioactive luminescence, but are no longer luminescent, can be seen to have virtually burnt the dial around where they were applied.

The hands were originally luminescent as was the dial spots. Often when vintage watches are restored the old non active material is removed and a modern non-radioactive material is replaced.

Images of the case

This inner screw holds in place the pusher which is spring loaded

The shoulders are soldered in place

Inner case hall marks and reference

The outer gold case is re-inforced by an inner metal ring

The inner metal ring is located in place by this screw

The cut out in the bezel both locates the position of the bezel and allows for space around the winding stem tube

Summary

In watchmaking history, the Valjoux calibre’s hold a special place. They were taken and adapted by many brands to different degrees of technical and aesthetic personalisation. The reason for their popularity was their strong and reliable construction. Whether used by Rolex or Patek Philippe, these calibre’s from this period hold their moment in time and will always be collectable timepieces.

Despite this watch being far from water or even dust resistant, it continues to function and with respectful manipulation and use can happily continue to be used for lifetimes to come.

To learn more about Rolex click on www.rolex.com